Guideline on Service Agreements: An Overview

Note to reader

About this Guideline

The Guideline on Service Agreements: An Overview provides program and service managers and executives with an overview of the key concepts and steps in establishing service agreements. A companion document, the Guideline on Service Agreements: Essential Elements, provides detailed advice with practical examples and templates that can be used to develop service agreements.

The Guideline is the result of extended consultation with departments and agencies, and is part of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS)’s efforts to support the development and management of service agreements. It is one of a series of guidelines to support client-centred service and service excellence, and forms part of TBS’ suite of service policy instruments. This Guideline supports the Directive on Internal Support Services and will also support organizations in pursuing consolidation and greater efficiencies in the delivery of services.

1. Introduction

Establishing service agreements is a sound management practice in any type of client / service provider arrangements when, for example, a Government of Canada service is provided by one department to, or on behalf of, another department. Service agreements are also recommended in other types of collaborative service arrangements where two or more departments collaborate jointly on a service or project initiative. In this Guideline, the term “department” applies generically to organizations listed in the Financial Administration Act (FAA), Schedules 1, 1.1, and 2. This Guideline supports the Directive on Internal Support Services and will also support organizations in pursuing consolidation and greater efficiencies in the delivery of services.

Specifically excluded from this Guideline is a discussion of service relationships between the federal government and an individual or private sector organization which are typically covered by a contract, grant and contribution agreement, or sales agreement/invoice. Although the principles and elements involved in a service agreement between two government organizations are equally applicable to service arrangements where, for example, an external firm delivers a service to one or more client departments, where an external firm or NGO delivers a service on behalf of a department, or where a department provides a service to an external client for a fee, these types of contracts and agreements and the related concepts of price and profit are not within the scope of this Guideline.

The approaches outlined in the Guideline reflect current best practices from the private sector, other jurisdictions, and consultations with government departments. The Guideline recognizes that although the use and applicability of service agreements should be standard government-wide, service agreements should be tailored to the circumstances and requirements of the participating departments, the various collaborative arrangements they may use, and the complexity of the service relationship. The goal of this Guideline is to give program and service managers and executives an appreciation of the key elements involved in establishing effective service agreements that support client-centered, well-managed services.

This Guideline should be read in conjunction with the following documents:

- Guideline on Service Agreements: Essential Elements

- Guideline on Service Standards

- Guide to Costing

- Directive on Internal Support Services

- Other Treasury Board policy instruments relevant to service delivery or related to governance, price, and performance.

The Structure of this Guideline

This Guideline is divided into the following sections.

Section 2 explains key concepts associated with service agreements.

Section 3 looks at how a service relationship is defined and then articulated in a service agreement, including a summary of the key elements that should be covered in a service agreement.

Section 4 outlines the different types of service agreements and where they are best applied, including the suggested form and format of agreements and the general process of development.

2. Key Concepts

What Is a Service Relationship?

Important!

Before initiating a service relationship whereby a department is providing a service to or on behalf of another department, the parties to the agreement are encouraged to ensure that they have:

- The legal mandate to provide the service.

- The authority to cost recover, if applicable.

- Revenue re-spending authority, if applicable.

- Delegated FAA authorities for sections 33 and 34 to the service provider as required.

- Any other necessary authorities, including authority to collect personal information.

A service relationship between two or more parties arises when:

- one party provides a service to another, typically on a fee for service basis (client/provider relationship); or,

- when two or more departments collaborate by pooling resources to jointly create and/or deliver a service or project (collaborative relationship).

What Is a Service Agreement?

Did You Know?

A service is the provision of a specific output, including information, that addresses one or more needs of an intended recipient and contributes to the achievement of an outcome.

Departments can use this definition of service to build an inventory of the services they deliver. Understanding what services are provided and details regarding these services are an important first step in service management.

A service agreement is a formal agreement between two or more parties that articulates the terms and conditions of a particular service relationship.

Service agreements serve three primary functions:

- Articulating the expectations of the parties to the agreement.

- Providing a mechanism for governance and issue resolution.

- Acting as a scorecard against which to examine performance and results.

Service agreements can enhance governance, accountability, and service quality by clearly defining roles, responsibilities, processes, and performance expectations. The practice of establishing service agreements is strongly recommended in any type of client / service provider or collaborative service relationship.

In most cases, the parties reach a thorough understanding of the service relationship before specific details found in a supporting service agreement are finalized. Aspects of the service relationship that are typically documented in a service agreement include scope, governance, operations, finances, performance, and implementation.

This Guideline outlines a flexible approach to developing service agreements tailored to the specific requirements of a particular relationship and/or the complexity or scope of the service relationship. Application of the approaches described in this Guideline should improve the consistency and clarity of service relationships across government.

When Should a Service Agreement Be Used?

There are many types of client / service provider and collaborative service arrangements where a service agreement should be considered. Examples of such arrangements include:

- Bi-lateral service arrangements where one department provides selected services (on a service-by-service basis) to one or more other departments. Although the provider may deliver services to more than one department or external client, each service is a bi-lateral relationship with little or no collaboration between the client departments or external clients. Bi-lateral service relationships can be found between small departments and agencies and their portfolio lead departments, in regional situations where two organizations are co-located or in close proximity to one another, in the provision of client-facing in-person, e-service, or 1-800 services by Service Canada on behalf of one or more departments, and in the hosting and management of corporate administrative systems. Typically the relationship is governed through a bi-lateral service agreement between the client department and provider department.

- Co-op sharing arrangements where a small number of participating departments pool resources (i.e., people or money) to fund a shared resource or a one-time project. Co-op sharing arrangements are most often found between groups of small departments and agencies seeking to achieve a degree of economies of scale in order to deliver equivalent service at a lower cost or a more effective service for the same cost. The arrangement is typically guided by the participating organizations through a management committee. Co-op services are usually housed administratively in one of the participating departments.

- Cluster group arrangements where a number of participating departments jointly fund and govern an ongoing service, a joint procurement, or a project. The main difference between a co-op and cluster group arrangement is one of scale. Cluster groups typically have a more sophisticated governance structure with Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM), Director General (DG), and technical committees. Cluster groups often create a permanent program office with a more formal work planning and prioritization process. Cluster Group arrangements are typically found around the management of human resource and finance and materiel systems (e.g., SAP, PeopleSoft, and Oracle). A Cluster Group may be administratively housed in one of the participating departments or at Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC).

- Shared service arrangements where a service, typically an internal service, is provided by an organization or unit created with a specific mandate to deliver that service to internal clients. The shared services model looks to create large-scale capacity and economies of scale. Services are typically transaction-focused and generally include the domains of human resources, finance, and materiel. Governance is through a Board of Directors. The service provider recovers cost from client departments who purchase services on an annual basis.

- Common services, mandatory or optional, are an activity of a common service organization (CSO) designated, in the Common Services Policy, as a central supplier of particular services to support the requirements of departments. Mandatory services are mandated either in legislation or policy. Departments must use the mandatory common services listed in Appendix E of the Common Services Policy. Departments may use optional common services offered by CSOs when it makes sense to do so. As a guiding principle, mandatory services provided by a CSO are funded through appropriations while optional services are funded mainly through cost recovery. Although customer relationship management and client experience feedback regimes are typically in place and there may be advisory governance committees, there are rarely formal governance structures through which client departments exercise direct decision-making power over the evolution of the service portfolio.

- Arrangements with other jurisdictions where a province or municipality delivers a service for or jointly with the federal government, or alternatively, where a department provides a service to a province or municipality in return for a fee. Service arrangements with other jurisdictions are typically in areas where a target group is served by a range of municipal, provincial, and federal programs, or where a range of municipal, provincial, and federal services are delivered in the same region, city, or remote area.

Important!

Depending on the underlying legislative or policy authority, whether the service provider is a common service organization under the Common Services Policy or not, and/or the funding mechanism in play (e.g., appropriation, revolving fund, or net-voting authority), fees or charges for services may be based on full costs, incremental costs, or some other agreed upon basis. For the purposes of this guideline, the term “cost” is used generically. Parties to a service agreement must determine the appropriate basis underlying the service’s fee structure.

The client / services provider and collaborative relationships noted above can and are being used for both the ongoing delivery of services and for the delivery of specific one-time projects.

Although the form and content of the service agreement should be adapted to the specific conditions of the arrangement, the principles and factors to consider remain the same.

The term “client” applies generically to both clients in a client / service provider arrangement and to participants in a collaborative service arrangement. The term “service provider” or “provider” applies generically to providers in a client / service provider arrangement and the lead department that is delivering a service within a collaborative arrangement.

This Guideline applies to client/provider arrangements in which a Government of Canada service is provided by one department to, or on behalf of, another department; when two or more departments collaborate on a service or project initiative; or when a province or municipality delivers a service for or jointly with a federal government department, or a department provides a service to a province or municipality. It reflects the current operating and policy environment and will be updated to reflect any legal and/or policy changes that may affect service agreements.

How Does a Service Contract Differ from a Service Agreement?

The Treasury Board Contracting Policy defines a contract as “an agreement between a contracting authority and a person or firm to provide a good, perform a service, construct a work, or lease real property for appropriate consideration”. Contracts constitute a legally enforceable agreement between the contracting parties and are subject to the requirements outlined in the Contracting Policy.

In contrast, a service agreement is a formal administrative understanding between the parties to the agreement. As one cannot enter into a contract with oneself, agreements between federal government departments (part of the same legal entity, the Government of Canada) are administratively binding as opposed to legally enforceable. Deputy heads typically sign service agreements on behalf of their department and are ultimately accountable for delivering on the commitments articulated in the service agreement. It is highly recommended that departments involve their legal services in the development and review of service agreements.

As noted, external service relationships typically covered by a contract, grant and contribution agreement, or sales agreement/invoice are not covered within the scope of this Guideline.

What Is the Relationship of Service Agreements to Risk Management?

Did You Know?

The Framework for the Management of Risk is one of the core Treasury Board policy and management instruments.

For the Government of Canada to continually improve its services, it is important to use a management regime that fosters efficiency, effectiveness, flexibility, innovation, and results. This need coincides with government’s desire to improve service delivery through collaboration, which carries an element of risk.

Service agreements are an important risk management and mitigation tool that helps deputy heads fulfill their responsibilities and accountabilities. Deputy heads should have a clear plan of how risk will be managed when entering into a contract or a service agreement particularly as they relate to their accountabilities. The complexity and level of collaboration should drive the risk management approach and the level of detail pursued. In addition to managing and mitigating specific service delivery risks (as identified in a horizontal risk assessment), an updated Business Continuity Plan (BCP) should guide how a partially or completely interrupted service will be restored after a disaster or extended disruption. Conversely, the ability to quickly adapt and add new services in a time of emergency, such as to provide disaster assistance or the ability to continue to provide services during such a time should be considered as needed.

3. Defining and Building the Service Relationship

A service agreement articulates a service relationship between two or more parties. Defining the service relationship, specifically the nature and scope of the services involved, the relationship’s governance and operations, the finances, and the performance measurement and reporting regime, is a necessary prerequisite to defining a service agreement.

Key Questions

Developing a service relationship typically involves answers to the following questions:

Important!

Typically, discussions around more complicated service arrangements take place in sequence over time, with documentation produced at the conclusion of each activity. In less complex, narrower scope arrangements, the parties may choose to simplify the process. Regardless of the approach chosen, it is important that the parties keep the end goals in mind throughout the process.

- What services am I receiving and for how much? What am I providing and what is the basis of recovery if any? Stable, long-term service relationships are based on win-win propositions. The client receives value for money while the provider successfully delivers the service while covering their costs through appropriation or some other basis of recovery. The parties should explore the scope and level of services, associated performance targets, potential for efficiency and effectiveness gains, and related financial arrangements.

- How will it work? Successful service relationships can “sour” over seemingly minor operational misunderstandings. Therefore, the parties should clarify governance arrangements, relative roles and responsibilities, related decision-making powers, approval processes, amendment and termination mechanisms, and put mechanisms in place to solve and/or mitigate issues in a timely fashion. The implications of client compliance with service provider standards should be fully understood.

- How do we get there? Implementation of a new service relationship has an impact on both clients and providers and often demands a level of commitment and resourcing that can stretch the capacity of both parties. Implementation of a new client/provider or collaborative arrangement typically involves changes in roles, responsibilities and processes, the implementation of new technologies or interfaces, the training of users and support staff, and the transfer and conversion of data. The parties should define the implementation approach, timeframes, responsibilities, and resource and skill requirements.

As the parties consider these questions, many of the related terms and conditions will be translated into a clause or a provision in a service agreement, most often under one or more of the following subject areas: scope, governance, operations, finances, performance, and implementation.

Key Inputs

A degree of preparation is required by both parties before they can productively sit down to discuss a service relationship.

Ideally, the clients should have a clear idea of the problem they are trying to solve or opportunity they are wanting to take advantage of and how they expect the new service relationship will help contribute to their objectives. They need to have a good understanding of their current baseline costs and their current and desired levels of service. If there are non-negotiable or unique business requirements (e.g., functions that must be retained, privacy or independence concerns, implementation timelines or deadlines, unique regional or functional requirements), these should be clearly identified. In short, clients need to be good buyers.

Ideally, the service providers will have defined their service offerings (i.e., service inventory), how the service is offered (e.g., basic and optional service packages), how the service is delivered (e.g., channels, minimum technical requirements, transferred and retained functions and business processes), the cost recovery model if applicable, and the implementation approach and activities. The service providers should also determine whether the new clients can be accommodated within their existing capacity or whether an incremental investment is required to expand their productive capacity.

In some cases, particularly when new services are involved, the clients and/or service providers may not have the information required to fully define all aspects of their service relationship. Service agreements can still be concluded in cases where more analysis or a pilot project is required. However, for the protection of both parties, a process to complete the analysis or pilot should be jointly formulated and articulated in the service agreement. The process should include appropriate off-ramps should the analysis or pilot indicate that a viable win-win relationship is not achievable. It is preferable that a non-viable relationship be abandoned at the outset before significant investments or contractual commitments are made.

What Services Am I Receiving and for How Much?

A service relationship is defined by its value proposition.

Service Relationships in Practice: An Example

Department X provides internal support services to a number of departments and agencies within its portfolio. Department X’s service relationship with each client department is characterized by the specific services it provides and the various governance and operating processes and protocols that apply. Each client department negotiates specific requirements for its services and Department X provides the services based on the terms and conditions set out in a service agreement.

For most clients, the service in question is already delivered in-house or by an existing service provider at a particular level of service and cost. Clients pursue new or modify existing alternative service delivery arrangements to expand the scope of a service, improve the levels of service, reduce costs, mitigate risks (such as skills shortages), or some combination thereof. A client’s value proposition is typically defined through the following questions:

- What is the scope and level of service I will receive and how does it compare to my existing service?

- Are there any service gaps (positive or negative) and what are the implications of those gaps?

- How much is it going to cost? Is it less expensive than my current cost?

- Are optional services / service levels offered and what are their costs?

- Are there other intangible benefits?

- Are any risks introduced through this arrangement? Does this arrangement mitigate one or more of my existing risks?

Typically, a service provider already delivers the service in question. Providers understand the scope and level of service offered and they understand their cost recovery model or price. The delivery model has been standardized and refined over time to take advantage of operational efficiencies and economies of scale. Providers usually take on new clients to realize greater economies of scale and efficiency. Service providers tend to avoid clients who do not fit their standard service and delivery model because unique requirements and one-off services can adversely impact efficiency and economies of scale.

A provider’s value proposition is likely to be defined through the following questions:

- Can my existing service offering meet the client’s requirements and expectations? Does the client have unique requirements and expectations that are outside my delivery model and capabilities?

- Can I cover my costs through appropriation or some other basis of recovery?

- Will this client’s requirements have an adverse impact on my operations or my ability to deliver my mandated activities?

- Can my existing capacity accommodate the client’s volumes? Will I need to expand my productive capacity?

- Are there any long term scalability and/or rust out issues I should consider?

- Are there other intangible benefits?

- Are any risks introduced through this arrangement? Does this arrangement mitigate one or more of my existing risks?

Clients and providers have both common and competing objectives. Finding a win-win proposition can be a challenge, but is a necessary prerequisite to a successful long-term service relationship. Although governance, operational, and implementation issues are time consuming, they are well worth the investment in time as the lack of a value proposition for either party is a potential show-stopper.

The process of articulating requirements, gaps, expectations, and risks forms the basis of the service relationship, details of which are typically described in the following areas of the service agreement:

- Scope, which starts with the identification of the services covered by the relationship and often expressed in terms of functions, processes, activities, or projects;

- Finances, which cover such items as the fee structure or resource pooling arrangements, cost transparency, variances and adjustments, and settlement arrangements; and

- Performance, which identifies outputs and outcomes the parties expect to achieve from the arrangement.

The Guideline on Service Agreements: Essential Elements provides detailed guidance and examples on each of these areas.

In many instances, particularly those involving complicated service delivery environments, the parties formally document their understanding of the proposed service relationship before proceeding with a discussion of the detailed governance, operational, and implementation arrangements. In some cases, an analysis of options and/or a feasibility study would be required before discussions about the management and operation of the arrangement can proceed. In complex arrangements, the resources and personnel to be assigned and the activities required to complete the service agreement should be discussed and agreed upon.

How Will It Work?

The mechanics of a service relationship are embodied in its governance and operating structures and processes.

The parties should discuss and agree not only on how an individual service will work, but also how the overall relationship will be managed. Details are typically defined through the following questions:

- How is the service delivered? What will be its processes? Which channels will be used? What about the hand-offs?

- What are the relative roles and responsibilities of each party with regard to the management and operation of the service? Where will decision-making authority reside?

- How is accountability most appropriately shared? Are any formal delegations required?

- How will disputes, issues, and problems be resolved? What is an appropriate escalation mechanism? What amendment and termination mechanisms are required?

- How will transaction approvals be handled?

- How will performance be tracked and reported? How will course corrections and prioritization be done?

- What governance and operational structures, processes, and decision-making powers need to be put in place to support the relationship?

The process of articulating the governance and operational structures and processes will form the basis of the operational relationship, details of which are described in the following areas of the service agreement:

- Governance, which typically deals with questions of “Why”, “Who does what?”, “Who decides what?”, and “Who answers for results?”

- Operations, which cover all the day-to-day activities related to the provider’s execution of the service.

The Guideline on Service Agreements: Essential Elements provides detailed guidance and examples on each of these areas.

Discussions on the development of a service agreement should establish common elements that will apply to any subordinate service level agreement.

Discussions about operational plans are based on what service the parties decide to include in the arrangement, the level of service needed, the level of resources required (financial and/or human) to be transferred between the parties, and the development of contingency plans.

Performance measurement and reporting activities serve as a scorecard and a means to monitor ongoing performance. This information allows parties to determine whether adjustments to the agreement are required and also permits the ongoing evolution of the agreement. The form and frequency of performance reports should be discussed and included in the service agreement.

How Do We Get There?

The implementation phase, where it exists, encompasses all of the plans and activities used to move responsibility for the delivery of the service from the client to the service provider. Implementation typically involves changes to roles, responsibilities, and processes, the adoption of new technologies, channels, or interfaces, the training of users and support staff, and the transfer and/or conversion of data.

In many ways, the successful execution of a service relationship depends on the care with which the implementation details are articulated and carried out. Schedules, milestones, performance objectives, and, where appropriate, detailed project or work plans need to be established to ensure all parties share common expectations about what implementation will look like.

Implementation efforts are highly dependent on the complexity of the service involved and the collaborative arrangement utilized. Implementation of a new service offering generally requires greater attention than does the implementation of an established service. Discussions may be unnecessary between parties renewing a long-standing service relationship. In some cases, the successful implementation of a large, complex, or mission-critical service may be included in a deputy head’s performance agreement.

In more complex arrangements where multiple services are being provided under a single master agreement (e.g., translation services for Department X), implementation details for individual services or projects are often captured in individual Service Level Agreements (SLAs).

Implementation details are typically defined through the following questions:

- What are the activities involved in the implementation process? What support is offered by the service provider?

- What are the typical timelines for implementation? Typical level of effort and skills required?

- What are the relative roles and responsibilities of each party in the implementation process?

- What are they key risks involved in implementation?

Answers to these questions are typically described in a service agreement. Detailed guidance and examples on implementation are provided in the Guideline on Service Agreements: Essential Elements.

As the service agreement takes effect, it is important that the transition from implementation to operations is well managed and remains aligned with each party’s objectives and commitments. The reporting activities and schedules in the implementation documents (e.g., SLAs) are a means to determine how well commitments are met under the arrangement.

In many cases, all the planning elements for a relatively straightforward service arrangement can be negotiated at the same time. More complex service arrangements are generally negotiated through a sequential, multi-stage process.

Checklist: Defining and Building the Service Relationship

Recommended Practice

- Undertake a joint planning exercise to define the service relationship

- Determine the governance and management regimes for each service and for the relationship as a whole

Considerations

- Number and scope of services included

- Service levels and performance expectations

- Length of the service agreement

- Roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities of each party to the arrangement

- Notice period and processes for a party leaving the arrangement or for terminating the arrangement as a whole

- Nature and complexity of the service arrangement

- Risks associated with the proposed service relationship

- Experience of the parties in developing and implementing service arrangements

- Implications to the organization of the implementation of the service arrangement

4. Developing a Service Agreement

Important!

Regardless of their complexity, it is strongly recommended that managers consult expert counsel, such as corporate and legal services, in developing their service agreements.

The speed and ease of developing a service agreement depends on many factors. Service agreements can be put in place quickly and easily when the service relationship is relatively simple, well understood, and there are few issues to resolve. However, more complex service agreements (e.g., to maximize use of resources, respond to government-wide planning activities, or support horizontal initiatives between two or more departments) normally require additional time and effort to complete.

The Guideline on Service Agreements: Essential Elements provides detailed advice, guidance, and practical examples and templates. A summary of key items is below.

Types of Service Agreements

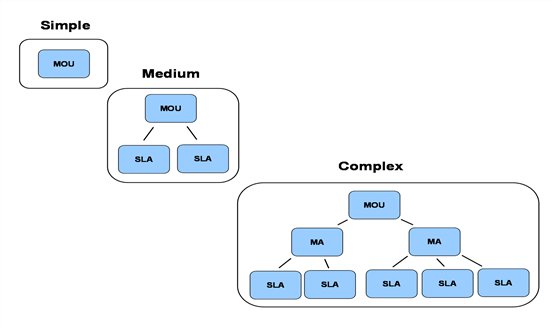

Although individual service agreements can – and often should – look very different from one another, they can generally be categorized into three types based on the complexity of the arrangement they are addressing. Service agreements may take the form of a Memorandum of Understanding, a Master Agreement, and/or a Service Level Agreement.

- The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) defines the broad parameters of the service relationship between the parties to the agreement, the service vision, and the exercise of decision-making authorities.

- The Master Agreement (MA) is an overarching document that sets out the services included, how the bundle of services will be managed, and operational details that are common to all services. The MA also lays the overarching framework for multiple service level agreements, typically one for each service covered by the MA.

- In most three-tiered service agreements, Service Level Agreements (SLA) establish the operating parameters and performance expectations between the parties to the agreements. Normally a SLA is established for each line of service or project.

The choice of agreement and their relationship to one another depends upon the complexity of the service relationship and service as depicted below.

Simple or One-tiered Service Agreement

Important!

Depending on the complexity of the service arrangement, parties may choose to combine the planning phases. Typically, negotiations for more complicated service arrangements (i.e., “three-tiered” service agreements) take place in phases, with documentation produced at the conclusion of each phase.

A simple service agreement is used when the service delivery situation is uncomplicated (e.g., roles and responsibilities are clear, obligations are readily identified and evaluated, and there are few or no risks). A simple service agreement can be as straightforward as a one or two-page MOU between two or more parties, if it addresses certain elements of scope, governance, the financial arrangements, and performance. Inclusion of service levels in some manner is strongly encouraged in even the most basic of service delivery situations.

Medium or Two-tiered Service Agreement

Where the service relationship, management, and delivery are moderately complex, service agreements are normally divided into two documents. The first document – often an MOU – describes the organizational relationships (including governance) and management processes that will regulate delivery of the service. It identifies the commitments the parties are undertaking and establishes the vision, mission, and mandate that frame the service relationship.

The second document, a SLA, delineates the operational specifics of the service, including clear, detailed information about the scope and service levels to be delivered. The SLA sets out detailed performance expectations, including service and performance standards, and acts as the basis for future evaluation activities.

Complex or Three-tiered Service Agreement

Complex service relationships and collaborative arrangements are most appropriately captured through a three-tiered service agreement, typically involving a MOU, MA, and one or more SLAs.

Choosing the Right Type of Agreement(s)

Service Agreements in Practice: An Example

As part of its service agreement with a client department to provide or arrange for overseas accommodation and support, Department X establishes one or more SLAs that address items such as communications, housing, office space, and security.

No single approach or format for service agreements is suitable for all circumstances. The appropriate form and format is determined by a variety of factors, including:

- Scope and significance of the agreement: Consider the range of services, products, or functions addressed by the arrangement and their impact on the parties’ ability to fulfill their mandates. Identify any limitations to the services under consideration.

- Complexity of the client/provider or collaborative arrangement: Assess issues around the type of arrangement, the number of parties involved, the complexity of any procurement required, integration with other departments, relative roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities, cost, and political visibility.

- Type of service covered: Consider the complexity of the function, line of business, or services included in the agreement.

- Term (start and end date) of the relationship: Assess the risks and impacts related to the duration of the relationship.

- Risk: Assess the nature and level of risks.

- Experience: Note the experience of each party in developing and implementing comparable services or collaborative arrangements.

- Implications of the change: Consider possible consequences for staff, managers, and the department as a whole, including the impact of disruptions on operational and organizational structures.

Respecting Official Language Requirements!

Remember that service agreements with third parties must be compliant with section 25 of the Official Languages Act and the Policy on the Use of Official Languages for Communications with and Services to the Public and respect the following principles:

- Any contract includes official languages clauses that clearly identify official language requirements with which the third party must comply;

- Any confirmation of the third party’s delivery performance includes compliance with official languages obligations.

5. Conclusion

When departments negotiate arrangements to work together or when they work individually to provide better services for internal and external clients, service agreements provide a means to promote the delivery of cost effective client-centred, well-managed service. They help reinforce accountabilities when one department provides service to or on behalf of another department by ensuring roles and responsibilities are clearly outlined and deputy heads have the correct information to discharge their accountabilities. Service agreements also increase the quality and consistency of service arrangements throughout the Government of Canada through the use of common structures, approaches, and, to some degree, processes. Together, these activities help enhance the management of service delivery and promote efficiency and effectiveness.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2017,

ISBN: 978-0-660-09777-0